Author: Kevin Daley

History According To Kevin Daley

Battle of Antietam

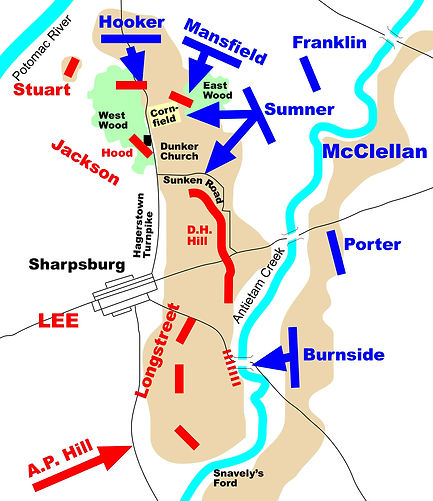

On September 17, 1862, Major General George B. McClellan led a vast Union force to meet confederate forces in Sharpsburg, Maryland for what would become the bloodiest single-day battle in United States history. General Robert E. Lee, the confederate commander whose army McClellan would soon face, had just won yet another significant battle for the South at Manassas, and now planned to use his ever-growing momentum to go on an offensive push North (“The Battle of Antietam”).

McClellan, who Lincoln had sent solely to stop the invasion, did not have an easy task. The Confederates had the high ground, positioned west of Antietam Creek, and went into the twelve-hour bloodbath with favorable odds. McClellan’s strategy was to flank Lee’s army on either the left or right, and upon collapsing one side, advance right down the middle of the Confederate force (Nardo 10). Various waves of Union Soldiers attempted to complete this objective, but a stubborn Confederate army did not concede any major advances to their enemies. This disallowance, however, did not come without sacrifice. At the day’s end, approximately 1,550 confederate soldiers were killed, only a small fraction of the South’s total 10,230 casualties (“Casualties of Battle”). The Union, which was never able to mobilize a centrally advancing assault, suffered massive losses as well, with 2,100 dead of an approximate 12,400 casualties (“The Battle of Antietam” and “Casualties of Battle”).

Bibliography

1. "The Battle of Antietam." National Park Service 19.9 (2014): 576. Web. 18 Jan. 2016.<http://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/upload/Battle%20history.pd>.

2. United States. National Park Service. "Casualties of Battle." National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 Jan. 2016. Web. 18 Jan. 2016. <http://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/casualties.htm>.

3. Brinkley, Alan. The Unfinished Nation: A Concise History of the American People. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2004. Print.

4. Nardo, Don. The Civil War. San Diego: Lucent, 2003. Print.

The battle ended as a Union victory. Although they had paid a hefty price, the soldiers of the North had weakened Lee’s army enough to force him back to Virginia, and so end his first invasion of the United States (“The Battle of Antietam”). The battle held a potentially war ending amount of strategic weight, as McClellan said, “...if we defeat the army arrayed before us, the rebellion is crushed, for I do not believe they can organize another army. But if we should be so unfortunate as to meet with defeat, our country is at their mercy.” Whichever side emerged victorious would not only be on the offensive, but also have a serious upper hand for the remainder of the conflict (Nardo 10).

The battle not only influenced the Union’s war effort by turning the tide of an otherwise taxing conflict, but also wielded enormous political power. President Lincoln had been waiting for such a Union victory as this to announce his newest piece of legislation, the Emancipation Proclamation. By declaring the Slaves of the South free, Lincoln now gave his cause the moral high ground, and in doing so, provided new motivation for his army (Brinkley 244 & “The Battle of Antietam”). This also prompted a perhaps unforeseen reaction as well, in making the war about the liberation of slaves; Lincoln strengthened the appeal of radical republicans, making it look as though they had had the right idea all along (Brinkley 244).

The Battle of Antietam was a dark, but necessary day in American history. Had Lee not been forced to retreat, he could have led an entire campaign through a weary, discouraged North, erasing any chance of the Emancipation Proclamation, and leaving the Union at the mercy of confederates.